Not much makes the world simultaneously bigger and smaller, but the World Cup boasts that precise, precious capacity. While celebrating our differences – all those songs, all those chyrons, all those haircuts – it also highlights our similarities – all those souls, all those feelings, all that love – which together compel our species into a single endeavour of collective bliss.

But rarely has rapture been as rampant as when Yordan Letchkov’s header gave Bulgaria victory over Germany at USA 94. His team weren’t even meant to be there; needing to beat France in their final qualifier, the score was 1-1 with 90 minutes played. But then out of nowhere a fantastic pass from Lyuboslav Penev found Emil Kostadinov racing towards the box … and he absolutely mulleted a sensational finish in off the bar. “God is Bulgarian!” hollered Nikolay Kolev in commentary. “God is Bulgarian!”

The travelling squad was a classic of the “small country” genre, melding exceptional quality, exquisite attitude and exhibition weirdness, along with the obligatory pair of players who were subsequently crap in England. Previously, Bulgarians had been forced to stay in domestic football until turning 28, but the fall of Communism allowed a brilliantly talented generation to develop abroad, then regather to lift a nation struggling with its new economic reality.

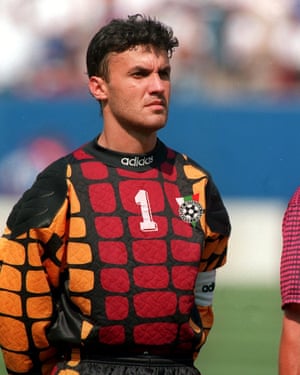

Captaining the team was Borislav Mihaylov, his defining feature a subject of conjecture to this day. Rationalist Maimonideans postulate that he underwent a hair transplant; spiritualist Nachmanideans presuppose he kept goal while balancing a syrup; either way, Reading fans hope never to hear of him again.

Mihaylov’s principal protector was Trifon Ivanov, famed for a phenomenally photogenic mullet-beard combo, wild shots from ridiculous distance, and the tank he drove about the meadows near his home. Also a fine defender and much-loved teammate, he was responsible for mediating between the squad’s Levski and CSKA factions.

In midfield, Bulgaria were particularly strong, with Krasmir Balakov a clever prompter and Kostadinov a goalscoring winger. But the key man was Letchkov, “The Magician”, his skill and strength elevated by aggressive, indignant entitlement.

And then there was Hristo Stoichkov Stoichkov – so good they named twice, so good they named him Christ. A piranha fish with dancer’s feet and tremendous moxie for his size, he invented agita where there was none and resolved matters as he saw fit, like Richie Aprile with a hangover. Where Roberto Baggio was the “Divine Ponytail” and Romário the “Little One”, Stoichkov was either “the Dagger” or “El Pistolero”, depending on the kind of temper he was in.

The draw was unkind to a country without a win in five previous finals appearances, Bulgaria lumped with Argentina, Nigeria and Greece. On top of which, the FA hadn’t paid the players’ $100,000 qualification bonus; a reduced amount was eventually transferred before their first game.

Which did not go well – Bulgaria were whacked by Nigeria – so Stoichkov resolved to give Greece “a good hiding, a serious thrashing”, scoring two penalties in a 4-0 win. “Beaten by that flat-footed poof Ivanov,” said Greece’s manager of his humiliating personal inadequacy.

To ensure progression to the knockouts, Bulgaria needed three points from their final game against Argentina – who’d had Diego Maradona sent home. “Without him they wouldn’t even win playing with twice as many players,” reckoned Stoichkov, and a 2-0 win earned his team a second-round meeting with Mexico, which they won on penalties. Back home, intense jubilation.

In the quarter-finals Bulgaria would meet Germany who, despite a sensational line in leisurewear stretching back decades, were the team that everyone else hated. World champions in 1954, 1974 and 1990, they added two European Championships to that in the process of reaching nine major finals, earning the nicknames “Turniermannschaft” – “tournament team” – and the more self-explanatory “Panzer”.

Muscular, mechanical, relentless and remorseless, they habitually overpowered more aesthetic outfits in as dastardly manner as possible. “I’m sorry for the other countries,” said Franz Beckenbauer after his team won Italia 90, “but now that we will be able to incorporate all the great players from the east, the German team will be unbeatable for a long time to come.”

But they were unimpressive in the group stages. In danger of tossing a three-goal lead against South Korea, when Berti Vogts substituted Steffen Effenberg, some in the crowd had the effrontery to cheer, so an affronted Effenberg effed them off by way of trusty stinkefinger – all good, clean fun and no harm done. Except the German FA had a new president with a name to make, so Egidius Braun – for that was his – sent Effenberg home.

Naturally, Germany still sneaked past Belgium and few gave Bulgaria a chance of beating them – they hadn’t been knocked out before the semis since 1962, instilling a calm confidence that inspired them and antagonised everyone else. They did not expect to win, they knew they would win, because winning was their right.

Which is to say that all that stuff about German football was true, but there was more to the animus than that. Not everyone had forgiven them for the war, and for those so minded, it was not hard to reminded of it by the way Die Mannschaft went about its business. International football is always political – how can any contest between different landmasses, featuring flags, anthems and people be anything but? – but international football against Germany was not just politicaller but politcallest.

The day before the game, the Bulgarian team celebrated the birthdays of Letchkov and Dimitar Penev, their manager, enjoying beers and tabs as was their wont. “Just relax,” Penev was reassured by the inimitable Ivanov. “With my bloodthirsty look, they will be scared to death. Rudi Völler will fall to the ground when he feels my breath.” Stoichkov, meanwhile, fraternised with a German cameraman. “Eins zu zwei zu drei zu drunn!” he informed him. “One to two to three to boom!”

Sure enough, Bulgaria set about Germany from the off. But an entertaining game was goalless before, two minutes into the second half, Letchkov’s rash knee-tap sent a Jürgen Klinsmann into a gleeful paroxysm of writhing brain-clutching; Lothar Matthäus duly punched home the eventuating penalty.

Germany had not lost a World Cup game from ahead since 1978 and that in a virtual dead rubber, so with the game listlessly drifting, Bulgaria’s horo looked up. But then, with 12 minutes remaining, Stoichkov coaxed a foul from Andreas Möller 25 yards from goal, right of centre and recalled that, on the day his daughter was to be six, she had asked him to do murder. “Dad, I know you’re always scoring goals,” he most definitely did not ventriloquise, “but because it’s my birthday tomorrow, score a goal for me. I’d really love that.” So he did, flighting the ball over the wall to assassinate Bodo Illgner at his near post. “Easy,” he recalled. “I hope it happens again that us Bulgarians are able to enjoy another player of great quality.”

Revitalised, Bulgaria pushed Germany back and found Zlatko Yankov out on the right, 35 yards from goal. He shimmied into a turn, advanced, measured a hopeful-looking cross towards the penalty spot … and suddenly the world seized its collective breath because there was the strapping Letchkov, with only Thomas Hässler, “the diminutive playmaker”, anywhere near him. Letchkov had grown up in Sliven, just 500 miles from Chernobyl, and attributed his youthful baldness to the radiation he’d experienced as a boy – though was less loquacious regarding the bushy side-pieces and tufty island which remained – and there was his pate in all its prodigiousness on the end of a run away from then towards the ball, belly-flopping a diving, glancing, planet-uniting header into the net.

Bulgaria exploded in pure identity, while the rest of the world enjoyed a moment of luscious joy in the misfortune of another – really, it’s surprising German has no word for such a feeling. In the event, though, the joke was on the rest of the world: two years later Germany won Euro 96 and, with typical Turniermannschaft fastidiousness, built one of Europe’s more successful, cohesive societies – which admittedly isn’t saying much, but every little bit helps.

As for Bulgaria, Stoichkov acclaimed “an easy win” before the team lost to Italy in the semi-finals; asked if God was still Bulgarian, he replied that he was, but that “the referee was French”. They were then thrashed in the third-place play-off by Sweden, before returning home to an amazing reception in Sofia.

Letchkov, meanwhile, became a national hero and eventually mayor of his hometown, before corruption landed him in prison; Balakov was forced to resign as Bulgaria manager after claiming not to have heard racist chanting during a match that was stopped twice; Mihaylov, who was president of the Bulgarian Football Union, was forced to resign as part of the same disgrace; and Ivanov died tragically young. Which is to say that, though football has an unrivalled ability to impact the world, the world also has an unrivalled ability to remain the world, so here we are.

• With thanks to Metodi Shumanov

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3ab6aXP

via IFTTT

No Comment