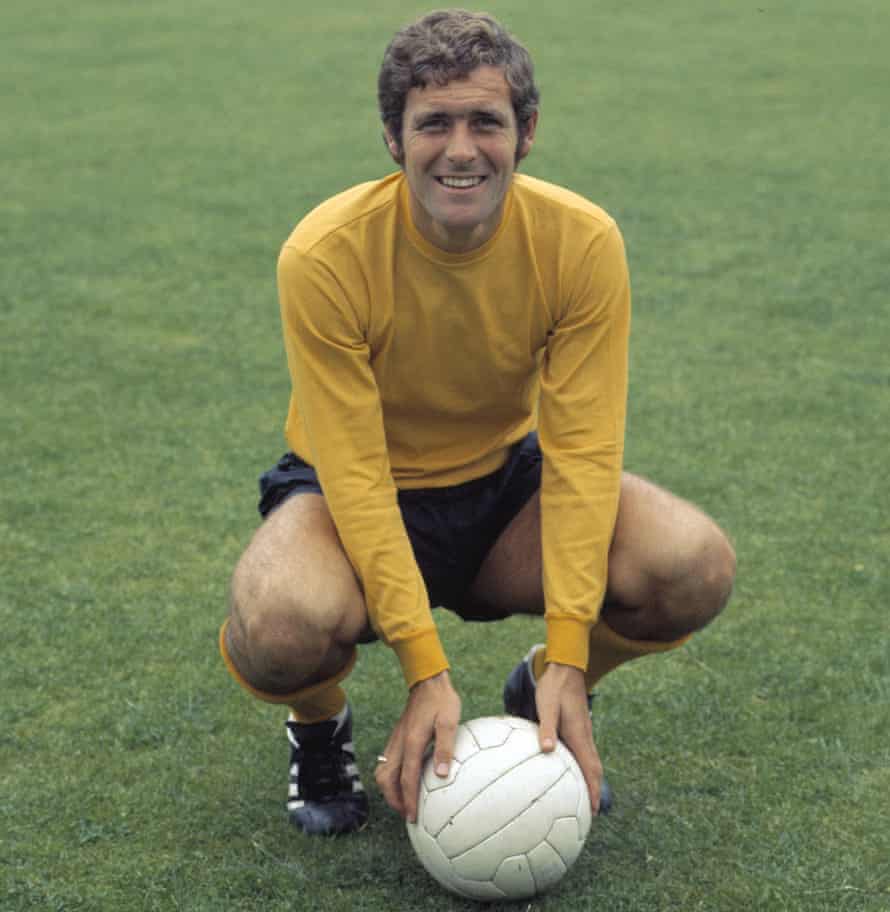

On 11 November 2002, the South Staffordshire coroner Andrew Haigh recorded a verdict of “death by industrial disease” in the case of the former England striker Jeff Astle who had died, aged 59, after years suffering with dementia. At that point there was already 30-odd years’ worth of anecdotal evidence that heading the ball caused brain trauma. The Astle verdict meant there was now an official recognition of a link. The Guardian called it a “landmark verdict”. An official at the Professional Footballers’ Association reassured the players, and public, that the PFA and the FA had “begun joint research” into how heading a football affects the brain.

“We cannot do anything about what has gone on in the past,” the spokesman said, “but maybe we can do something about the future.”

Eighteen years into that future, on 15 October 2020, the North Wales coroner John Gittins reached the same verdict in the case of the former Wales midfielder Alan Jarvis. It was the first such case since Astle’s. Jarvis’s family said at the time that they felt the authorities had been trying to “sweep the issue under the carpet”. The Daily Mail called the case a “landmark verdict”. And in the weeks afterwards, as the relatives of more and more retired footballers spoke about how their families were suffering, an official at the PFA came forward again.

The language was more urgent now, and came with a clear acknowledgment that the game had a problem, but it still ended with the promise that the union and the FA “were committed to funding further research”. Which sounded wearisomely familiar. “All scientific work is incomplete,” wrote the epidemiologist Sir Austin Bradford Hill, who was instrumental in establishing the links between smoking and lung cancer. “Whether it be observational or experimental. All scientific work is liable to be upset or modified by advancing knowledge. That does not confer upon us a freedom to ignore the knowledge that we already have, or to postpone the action that it appears to demand at a given time.”

A lot changed in those last two decades. There has been progress in football, and across all contact and collision sports, but the question of whether more could have been done sooner, whether sport should have gone further, faster, remains. It seemed to hang over the opening day of the digital, culture, media and sport committee’s inquiry into concussion in sport on Tuesday. You could hear hints of it in the MPs’ questions about who was funding the current research, and how much they were paying, whether there was material out there that hadn’t been published, about the workings of the Concussion in Sport group, and whether we need more transparency in research.

It came up directly after the neuropathologist Willie Stewart described football’s current concussion substitute protocols as “a shambles”. The Astle case was 19 years ago, said the committee chair, Julian Knight. “Yet we are talking about football protocols being ‘a shambles’. Why are we letting people down in this way? What is the problem in terms of our sporting bodies?”

Stewart said he shared Knight’s “frustration”, but preferred to look forward: “The challenge is not to make the same mistake again, where we all get together in 20 years’ time and say: ‘What has happened? Nothing!’”

This is an argument that comes up a lot in conversations with, and between, the growing number of academics, campaigners and researchers working in this field. There’s a theory that the reason the pace of change has been so slow is because the threat of litigation has put the governing authorities on the defensive, that the worry about whether they will be blamed for what they did wrong has made them reluctant to engage with suggestions about what they might do right. Advocates argue that everyone involved needs to take a more collaborative and constructive approach. It’s an idea that underpins some of the new campaign groups that have been set up in recent months, such as Head For Change.

Which figures. Back is not the best way to move forward. Only it does leave a lot of awkward questions unanswered. Questions such as, to pick one of many, what became of the work published in 1998, four years before the Astle verdict, by a team of researchers working in the Netherlands under Dr Erik Matser? The Guardian reported at the time that Matser’s team had found clear evidence that “heading a football can cause long-term brain damage”. One of the co-authors explained: “The mental impairment of the players is subtle and would go unnoticed by many people, however this type of brain injury may last forever.” In the long term, though, Matser’s work didn’t lead anywhere. He has his own ideas about what happened and why, which he has spoken about in a recent interview with the Dutch newspaper NRC.

Sign up to The Recap, our weekly email of editors’ picks.

The inquiry itself already feels too small, and underresourced, to dig into these issues in this kind of detail. Ninety minutes into the opening session the chair was already asking interviewees to “keep their answers concise” because “we’re relatively short of time”. There’s so much to cover, complicated questions of science, sociology and policy, across so many sports at youth, amateur and professional level. It has made for some awkward moments, with neurologists asked to provide expert testimony on issues of public health policy, and population psychology, and meant there have been some conspicuous gaps in the range of topics covered.

It is valuable work. But, 19 years after the Astle verdict, it still feels like late in the day to be beginning all over. And we’ll have to wait and see whether, this time, it leads to a real step forward in how sport handles these issues.

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/2OLNl6L

via IFTTT

No Comment