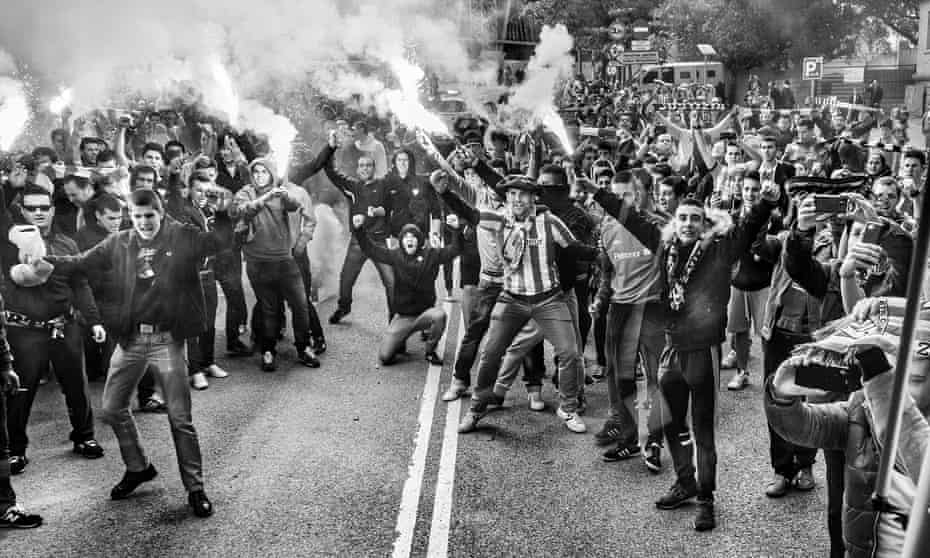

Football looks different from where Ernesto Valverde is. “The idea was to change the focus,” he says, which he always has. This week a photographic exhibition opened at the Ernest Lluch Kulturetxea in San Sebastián. Made up of black and white images in 1m x 1.50m, on linoleum and bolted to the wall to give an industrial, uncomfortable feel befitting the world it captures, the collection offers a portrait of the game from the other side through the lens of the former Barcelona manager.

Valverde didn’t always plan to be a manager. Having studied at the Institut d’Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya while a player, he prepared for a photographer’s career but football has a way of drawing you in, expressed in his pictures. Twenty uninterrupted seasons he spent coaching, taking Espanyol to the Uefa Cup final, Athletic Bilbao to their first trophy in 31 years and Barcelona to the double, until the Catalan club sacked him in January 2020, top of a league they haven’t won since.

His compact accompanied him. In 2012 he published his first collection and another book follows next month, while the exhibition is a selection of photos taken over a decade in football, partly inspired by his time at Olympiakos, where sport and sociopolitical issues came together. “I could tell a thousand stories,” he says, of “a place where they live football passionately, to put it mildly”. Flares. Half-times an hour long. Physical tension. “I worked out quickly it was a good idea to win.”

He did: having originally gone reluctantly, Valverde won three league titles and two cups. He also saw something, “a door opening”, an idea: “fans don’t go to games to watch, they go to participate”, Nothing mobilises like football. “La vida a lo bestia,” he says: roughly, life only wilder, exaggerated. On tour in the US and Japan with Lionel Messi and Neymar, it was like Beatlemania. His photography, much of it from inside the bus, turns on the crowd at once amorphous and individualised.

“You have all these people looking in, many taking; I took photos from the inside looking out,” he says. “The direction changes but I don’t want to distance ‘us’ and ‘them’ because ultimately it’s the same thing: all this paraphernalia is part of the same stage. The concept of popularity needn’t be football and the object is them, not us. I’ve never taken the camera into the dressing room.”

The photographs project an imposing power, which is perhaps part of the point, and helps to explain Valverde as a coach. To see his images and listen to him talk is to grasp some of the significance of human and environmental management. Enclosed on the bus, this kind of bubble, looking out on a living expression of the pressure, the responsibility for people’s happiness must be overwhelming. “No,” he says. There’s a pause, a laugh. “Well, it’s stressful inside. But if you think like that, you have to retire the next day.”

If his photos depict the scale of it all, one of the things that sets Valverde apart is his ability to dedramatise football, rationalise, filter out the noise, normalise it. Success is also built on an ease, a capacity to ride waves apparently unmoved by the coming storm, thus guiding others through it. Witness how quickly the cracks split open when he left Barcelona, the lid on crises removed.

“Nah,” he says, which he says quite often. “Football has become this thing we all live off and through. It’s a show, this great drama, the intrigue. Is this coach going? Will that player be defenestrated?” he says. And that’s despite not knowing the half of it. “The problem is you know too much,” Valverde says, cracking up. “They also ‘know’ things that aren’t true.

“You get this idea: ‘Bloody hell, it’s the end of the world if we don’t win this weekend.’ And you don’t win and on Monday, life goes on. It’s this incredible crisis, a real mess. Don’t worry, there’ll be another one along to cover this one. And the week after, another. You get to the end of the season and it’s the final judgment. But then: cut it off, chuck earth over it and another season starts. Tomorrow the sun rises. A new season, hope, excitement, and all that …”

There’s another smile. “Wait, wait, I haven’t finished,” Valverde protests. “Having said all that, I’m one of those that’s permanently there, bound up in all that, and it’s stressful, eh. You step back and rationalise it, sure, but inside, bloody hell. ‘We’ve got to win.’ There’s a tension that’s the hostia, unbelievable. If not, you won’t win. Rationalisation is one thing, but you have to be there. And being there is different. The whole thing takes you.”

Until you’re out again. The 4-0 defeat at Anfield did the damage, Valverde describing a game that “wasn’t real” where the disasters of previous years came back and “there’s a moment of instability, and at a ground like that”. But he continued eight months more, the club sticking with him, if not always by him. Perhaps he should have walked, with hindsight? “There are moments when you think, well, maybe,” he says, “but once you judge it, no. Football always gives the chance for ‘revenge’.” In the end, he was denied that chance, sacked after defeat in the Spanish Super Cup.

Photographs showed him smiling behind the wheel, waving as he went. The situation had become unsustainable, the pressure intense, sometimes absurd. Had it reached the point where the sack was a solution, something to want?

“No, no, no, there’s always a part that fights, that wants to show your worth. You think: ‘Wait.’ There are lots of crises and you think you can overcome this one too. Why wouldn’t I think we can still win the league? Our very first game, we had lost the Super Cup 5-1 to Madrid. Bloody hell. You’re affected, hit. And then …”

And then Barcelona went on to win the double. The next season they won the league. He didn’t make it to the end of the third.

“I know the meaning of what I say but if people are looking for you there’s nothing you can do,” he says of that parting smile. “There were loads of photographers and you’re not going to go out there with a face: ‘Oh, that poor thing.’ I don’t want anyone thinking that. Let them interpret it however they want, what does it matter?

“You stop, you breathe. You’ve been living with those demands, the tension for so long – not just at Barcelona but at Athletic. You need time. A certain solitude, distance. And then there’s a pandemic. It’s not that I locked myself away; it’s that everyone did. You avoid football for a bit, and then football goes and disappears.”

Fifteen months have passed now, the longest Valverde has ever been out of the game. There hasn’t been a word. Just silence. “Well, I suppose by doing this interview …” he says, apologetically. But there have been no recriminations, excuses, or sales pitch. Even though, champions two years running, top when he left, Barcelona haven’t won the league since.

“And?” he says. And it’s two league titles. “Yeah, but I know that.” Do others? Those titles feel unappreciated. “Look, this ‘appreciated’ thing. I appreciate those leagues. How could I not? There are people here: ‘We won the league, meh.’ But I valued it, of course I did. There are people who think it’s not enough. OK, but I can’t change their opinion.”

Photography has filled his time. Could football call again? “If there is something that motivates me, yeah, I could be tempted,” he says. “Things have come up that I turned down. The idea of going abroad is attractive: something different.” England? “Could be. I wouldn’t mind trying it. You get the feeling that there’s a respect there for what the game is.”

Ah, the game. For all the noise, for everything that goes with it, that’s part of it, as Valverde’s photographs convey, there’s always the game itself, still pure. “Yeah,” he says. “It’s what we like in the end. It’s what I like, at least. That’s why we’re here.”

Beste Aldea, organised by the Fundazioa Real Sociedad and the Fundazioa Athletic Club, will be at the Ernest Lluch Kulturetxea in San Sebastián until 4 September and the Zabalguneko Eraikina in Bilbao from 15 September to 28 October.

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/2RsZa3G

via IFTTT

No Comment