The chase begins frighteningly early. Often years in advance and usually when the object is still a child. Jude Bellingham and Gio Reyna were scouted at 14. Erling Braut Haaland first appeared on the radar in 2016, more than three years before he signed. Age-group games are surreptitiously attended. Targets are identified with surgical precision. Next: the charm offensive.

Introductions are made. Interest is subtly registered with parents and agent. Replica kits and club merchandise start arriving in the post. The prospective player is invited to Germany to watch a game in front of the heaving, haunting roar of the Yellow Wall (pandemic permitting). No gaudy blandishments; no super-yachts; no suitcases full of cash. As the sporting director, Michael Zorc, likes to put it, Borussia Dortmund don’t need to make grand promises to their teenage hopefuls. They just point to the team sheet.

Thus it was that on the first day of the Bundesliga season, Bellingham – a 17-year-old with one season of Championship football under his belt for Birmingham – made his debut in central midfield against Borussia Mönchengladbach, setting up a goal for the 17-year-old Reyna in the first half. In the second half the 20-year-old Haaland secured a 3-0 victory with two goals, the second assisted by the 20-year-old Jadon Sancho. Dortmund’s attacking quartet thus had an average age of 18 years and 11 months: four of Europe’s most exciting young attackers, who have entrusted their formative years to the BVB star factory.

In other circumstances, at bigger clubs, the path to first-team football might have been blocked. They might have ended up warming the bench, fighting for scraps. Bellingham and Haaland were both enthusiastically courted by Manchester United. Reyna was being tracked by Bayern Munich. Sancho sensationally left Manchester City in 2017 before he had played a senior game. All chose Dortmund, lured by the promise of immediate first-team football and rapid career development: a sort of elite footballing university where teenagers can try new things, find themselves, before going out into the real world.

This is the Dortmund Way: the aspirational strategy that has won admirers across Europe for its ability to buy young, sell young and turn a fabulous profit in the process. Ousmane Dembélé: signed for £13.5m, sold to Barcelona for £124m after one season. Christian Pulisic: plucked from obscurity, sold to Chelsea for £58m. Sancho, signed from Manchester City for £8m, will cost Manchester United more than £100m if they want to bring him back to England.

Of course these are just the successes. But even the relative failures show up in green on the balance sheet. The much-hyped Danish prodigy Jacob Bruun Larsen was sold to Hoffenheim for £8m. The defender Matthias Ginter never quite kicked on but still turned a 70% profit when he left for Borussia Mönchengladbach. The “Turkish Messi” Emre Mor was signed for £9m, lasted one disastrous season, and yet still sold to Celta Vigo for £12m.

And the Dortmund influence is clearly visible in the recent recruitment of clubs such as Lille, Leicester, Arsenal (who hired Dortmund’s chief scout Sven Mislintat in an attempt to replicate it) and even Real Madrid. Ostensibly, it’s a virtuous circle. The club get one of the world’s best young players. The player gets an education. The fans get treated to fast, scintillating expressive football. Everyone wins.

That is, as long as you are prepared to stretch your definition of winning. Since 2012, European football’s “model club” have raked in £378m in sales from players who were signed under the age of 21. On the pitch Dortmund have won a grand total of one cup, reached one Champions League final and finished a cumulative 149 points behind Bayern Munich, who they face in the German Super Cup final on Wednesday.

So does the Dortmund model work? Is this just a medium-sized club in a world of giants, doing the best it can, “rolling the stone up the hill each year, like Sisyphus”, as the chief executive Hans-Joachim Watzke puts it? Or are they simply a glorified feeder club, a business hustle, a cold production line where everyone is basically passing through?

Perhaps, as they say, it is a bit of both and in a sense these are questions that strike at the fundamentals of the game. What constitutes success? What is a football club actually for? Certainly any objective assessment of the Dortmund model needs to acknowledge not only the prevailing financial landscape but also the science and the romance at work, the brazen optimism of taking a punt on a young, uncut gem and the brazen cynicism of the logic behind it.

The roots of Dortmund’s strategy lie in the financial crisis of the mid-2000s that almost forced the club out of business. When Zorc and Watzke took over, their policy of signing untried young players (an “absurdly youthful team”, declared the Süddeutsche Zeitung) was driven not by idealism but by penury. Under an innovative manager called Jürgen Klopp, Dortmund built a Bundesliga-winning squad with an average age of 23.

As the golden generation were picked off, new generations were sourced from far and wide. Now Dortmund actively sell themselves to potential prospects as a springboard club, a shop window: on average around half the team are replaced every season. How does a club build anything in this maelstrom of constant renewal, constant churn?

The former Bayern Munich president Uli Hoeness recently argued that Dortmund’s policy of signing young players “for business reasons” was why they had failed to mount a consistent title challenge. “How is a player supposed to absorb the DNA of a club if he feels he is an object of sale?” he asked. “As long as Dortmund don’t change this strategy, I don’t think they will get that extra 10% to perform well in important games.”

Naturally, Hoeness was being characteristically mischievous and his comments drew an angry rebuttal from Dortmund. Yet it was the club’s managing director, Carsten Cramer, who admitted in an interview with the Financial Times in 2018 that “it’s not part of our DNA to be obligated to be number one”. Which may be a realistic analysis of operating in the semi-permanent shadow of Bayern. Even so, it rather invited the response: well Carsten, certainly not with that attitude.

In a way, United’s protracted pursuit of Sancho may bring all this to a head: a test not just of United’s determination to obtain the world’s best players but also Dortmund’s resolve to keep them. With two years left on his contract, they can certainly afford to play hardball. Will they hold firm, make a statement that they no longer need to sell?

Or in a Covid-era market will they ultimately take the money and start again? There is certainly plenty of talent rising through the ranks: Youssoufa Moukoko (15), Bradley Fink (17), Immanuel Pherai (19). Meanwhile, Dortmund recently secured a deal for Manchester City’s 16-year-old forward Jamie Bynoe‑Gittens, described as “the new Jadon Sancho”. That’s the thing about cycles: they can be royally tough to break.

Winds of change

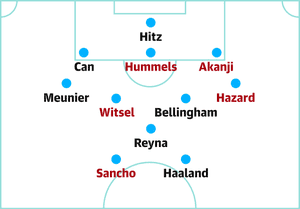

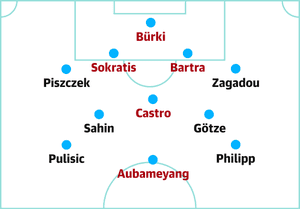

Dortmund opening-day Bundesliga starting line-ups 2016-20 (unchanged in red):

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/30gpKy4

via IFTTT

No Comment