About 3am one morning in the summer of 2011, when he was still only 23 and his promising career at Arsenal had begun to slip away, Nicklas Bendtner arrived at his favourite casino in London. “I’m way too drunk to sit at a table,” Bendtner remembers. “That much I get. But roulette is a different matter. Red, black, red, black. How hard can it be?

“After 90 minutes I’ve lost £400,000. Money I don’t have. My bank account is overdrawn and I’m bankrupt if my luck doesn’t turn. I stagger into the loos and splash water on my face. Then I find a cashier and get another £50,000 of chips.”

This unsettling memory is one of many moments that make Bendtner’s autobiography such a sobering insight into the lunacy a young footballer can suffer if he loses his bearings and is seduced by the empty glamour and wealth of the Premier League. Seven years later, after Bendtner had been left out of Denmark’s 2018 World Cup squad, he “sat on the shitter blubbering.” In his dejection he accepted that: “I became too fond of the lifestyle that came with the money. I want to go back in time and hit that young lad on the head with a hammer. Make him understand what a chance it is. That he has something special – something he has to look after.”

Now, sitting on a sofa in Copenhagen alongside his friend Rune Skyum-Nielsen, the Danish journalist who helped him write his book as a brutally candid and ultimately moving lament of the mistakes he made and the lessons he learned, Bendtner nods ruefully. “There’s definitely some regret I didn’t take my career in a more positive way. Looking back definitely gave me upset because there are moments which were very hurtful and difficult to talk about. But I couldn’t just write another sports biography where I was praising myself. Luckily I trusted Rune completely and could open up and say: ‘There’s only one way I can do it and that’s with complete honesty.’”

Bendtner pauses when I ask how he felt after losing £400,000 in the dizzying time it takes to play a football match. “When you’re more or less broke it makes you think: ‘It’s got to stop.’ I was down £400,000 but ended up winning some of it back, actually.”

As dawn broke that morning he had cut his losses to £20,000. He had been incredibly lucky, but the experience shook Bendtner. “It was too risky – even for me. It was the wakeup call that helped break that spell. I’ve never been a guy who cares about money as a way of showing off. At first it was more about the fun and being with people you like.”

Bendtner explains the illusory high he sometimes experienced in the casino. “When I was injured, and couldn’t get the excitement from that absolute living-on-the-edge feeling on the pitch, gambling gave me adrenaline. Obviously the higher the risk, the higher the adrenaline. So you go for high stakes.”

Four years earlier, aged 19, Bendtner had experienced the most euphoric burst of adrenaline when, less than two seconds after coming off the bench, he scored the winner against Tottenham as he met a Cesc Fàbregas corner with a towering header which has gone down in Arsenal folklore. It set a Premier League record for the quickest goal ever scored by a substitute. For Bendtner “it was like being 100% accepted into Arsenal. You’ve just scored your first Premier League goal and, because it was against Tottenham, you couldn’t have written it better.”

That header was sealed by the athleticism, power and skill which convinced Arsène Wenger that Bendtner had the ability to become a key player for Arsenal. His talent meant he had left Denmark to join Arsenal at 16. Bendtner was driven by a deep sense of self-belief and even entitlement. In later years, when his extravagant conviction became mired in his taste for the high life, he was ridiculed as Lord Bendtner. But it’s important to understand his background.

He grew up on the gritty island of Amager, close to Copenhagen, and opportunities were limited. Bendtner is proud of his feisty home. “Amager is for the lower-classes and it’s always been looked down on by people from Copenhagen. It’s called Shit Island because of the sewer system [as the island was used to dump latrine waste until the 1970s]. It’s quite a tough area but people from Amager help each other.”

Despite the unglamorous surroundings Bendtner grew up in a family where self-effacement was alien. “The Bendtner Family’s 15 Rules” were pinned to the fridge. Rule One: “You ARE to think you are something special.” Rule Two: “You ARE to think you can do what you want.”

Yet his father did not set him a good example. On the touchline his dad always blamed someone else for Bendtner’s mistakes. It skewed his thinking and Bendtner admits “the feeling of knowing best – no matter what – still haunts me.” He has “got better at saying sorry. But it’s something I’m still working on because it doesn’t come naturally.”

More poignantly, “the way I experienced the love of my father was when I succeeded at football. That self-belief was a way you got rewarded. In the way he always had my back, he was the most amazing father. But his way was not always correct and once I became a professional and earned a lot of money that tipped the balance in our relationship.”

Bendtner writes that, “Dad got weak when the money got big.” He shakes his head when I ask if his father has discussed the book with him. “No. I haven’t spoken to him in many years.”

The need for a steadying influence was obvious as Bendtner partied hard and frittered away his money. Wenger is highly intelligent and compassionate but could he have taken a harder line to help Bendtner? “It’s difficult because he could not take the time to just focus on one person. I think if I had a strong figure in my background that could have made the difference. But Arsène and I had a good relationship and I have tremendous respect for him. I don’t blame him for anything. He was always honest and he understands there are things I did that I’m not proud of.”

He ended up with his Lord Bendtner tag as contradictory stories of his swaggering confidence and errors of judgement escalated. “I wanted to express myself as a person on the pitch and I needed self-belief. How I then became a figure in the media was due to some of the antics that happened. But I never put myself in front of the team or tried to be a guy that I wasn’t. I was being truthful to myself because I don’t try to be any ordinary person. I want to give my opinion.”

Skuym-Nielsen leans forward. “What was interesting for me as an interviewer is that I’ve met lots of sports people and when you ask them a question they always think about how to make the least noise. Nicklas is very different because he’s giving you an honest answer. People were mocking him on Twitter, and still are, for answering a question as to whether he wants to be one of the best strikers in the world. Of course he wanted that and at the time he was scoring lots for Arsenal, in the spring of 2010 and also in the Champions League.”

His club career stuttered – amid loans to Birmingham City, Sunderland and Juventus before transfers to Wolfsburg, Nottingham Forest, Rosenberg and Copenhagen. Yet he produced his most consistent performances for Denmark and scored a Danish record of 30 goals while winning 81 caps. “I always felt my teammates believed I could make a difference. And my manager for most of my time with Denmark was Morten Olsen. He understood me better than any other manager. Even if he heard about something he would call and ask why did I think it went wrong? How do I feel? How’s my family? He wanted me to improve as a player and a person.”

He was on the verge of accepting an offer to play in China when the Covid pandemic struck. Despite his regret at not fulfilling his potential, “I can honestly say that, apart from my son being born and spending time with him, nothing gives me greater pleasure than playing football. It’s now difficult with Covid. If something comes up as a player I will look at it. If it doesn’t, I’m preparing for the next chapter.”

Bendtner, who is such a celebrity in Denmark, is now participating in a reality television show with his girlfriend – the model Philine Roepstorff. “It’s been running for nine months. People like it because it’s like my book. It’s very honest. We’re not just showing a perfect life. We’re showing a proper relationship with ups and downs.”

More intriguingly, Bendtner is preparing to become a football manager. “It’s my ambition right now and I’m starting a management course in December. I’ll have to do the exams first but luckily I have lots of good friends in football where I can gain experience.”

Will the mistakes he made as a player help him to manage young footballers? “I think it will be one of my strengths. I will have the awareness about where people might be in their lives as I’ve experienced it myself. I’m also lucky to have played under some great managers so maybe I am one step ahead in some ways.”

He is a less obvious managerial candidate than his former teammate Mikel Arteta whom he describes as having “an iron will almost unlike anything I’ve ever known.” Bendtner also praises Arteta for “never giving anyone a bad conscience” as a team-mate while “his commitment, determination and leadership was without question. He was the one who was always going down that [managerial] road and he was a guy you could go to for advice.”

Does Bendtner still follow Arsenal – as he did when he was a boy? “I watch all the Arsenal games I can and I’ve even got this thing that, when something happens in the game, my phone goes ping. So I’m still following Arsenal.”

It almost sounds as if Bendtner is at peace with his troubled past. “Yes, I feel proud of what I achieved and I’ve lived an exciting life. I’m only 32. I have much more life to live and many goals I’m trying to reach. Like most professional football players who come to the end, the best way to look at it is that I still have two-thirds of my life ahead.”

After everything he has learnt from the first third Bendtner is entitled to move on from regret. When I ask what he might have achieved if his younger self had heard himself talk now, he sounds only briefly wistful. “I had dreams and hopes and I could have done more.”

Bendtner pauses. “But I don’t want to make any presumptions and dig a hole yet again.” He laughs as the ghost of Lord Bendtner retreats into the distance. “That’s a very mature answer …”

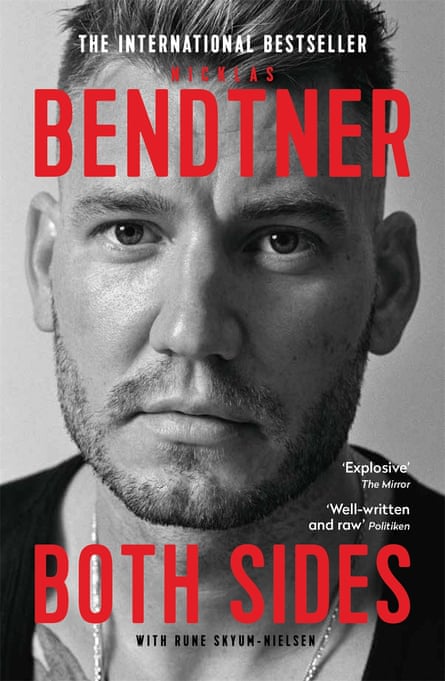

Both Sides by Nicklas Bendtner and Rune Skyum-Nielsen is published by Monoray.

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3nDhOkK

via IFTTT

No Comment