Football can be cruel. Even the greats are made to suffer. The narrative which has always been put out there is Ajax rejected Johan Cruyff and reneged on a contract. They didn’t. However, they deliberately forced Cruyff’s hand, perhaps attempting to embarrass the player, hoping, and knowing, he would not accept the standard contract and they could stop the massive gate payments. It could be true that they had decided he was past his best and despite everything he gave the club, he was no longer of any use, aged 36. But Cruyff felt the hiatus in the US had extended his career.

The time might have been right, therefore, to go back and speak to Feyenoord. Cor Coster [Cruyff’s father-in-law and agent] had established great contacts at De Kuip, and they had speculatively suggested if the Amsterdammers were having second thoughts or playing hardball, they would be willing to match a similar gate-based deal. When the insults started flying, and it became clear Ajax didn’t want Cruyff, Feyenoord’s proposal came back into the mix. Initially, the proposal might have been filed away under ‘audacious’. Cruyff couldn’t ever sign for Feyenoord. Then when they broke it down, he thought: why not? It would be a challenge. Who were Ajax to treat a legend so shabbily? Feyenoord’s stadium was bigger and held 47,000.

Cruyff clarified the whole saga in My Turn, when he explained, in detail: “At the end of the 1982-83 season, I signed for Feyenoord, Ajax was still my team, but the people running it [Ajax] refused to go along with me. I heard they were saying I was too old and too fat and still putting on weight. I had to deal with all their objections. And they also demanded that I should be satisfied with a normal salary and of course, I wasn’t.” With that, Cruyff’s pride and sense of wrongdoing took him to Rotterdam.

By 1983, Feyenoord had toiled and struggled as lesser sides overtook them. Feyenoord were the first Dutch team to win the European Cup, beating Celtic in the 1970 final, in Milan. But by the early 1980s the feeling among Dutch football fans was even Feyenoord weren’t Feyenoord anymore. They were now another big city side who had struggled and hadn’t won a league title since 1974. Clubs like PSV Eindhoven and AZ Alkmaar had joined the party. Some of their form in the seasons before Cruyff’s arrival was poor to average. In 1979-80, 1980-81 and 1981-82 they finished fourth, fourth and sixth respectively.

Cruyff’s move to Feyenoord could be compared in the modern era to Lionel Messi signing for Real Madrid, or more realistically, in pure football terms, Mo Salah leaving Liverpool to sign for a struggling Manchester United, toiling around fifth or sixth, winning the league and cup double, and being named player of the year. (For clarity, the Dutch Player of the Year is the Dutch Football Association’s award and is voted for by fellow professionals from the top two divisions. This was won by Ruud Gullit. There was also an award voted by influential newspaper De Telegraaf and football magazine Voetbal International, a prestigious press award called the Gouden Schoen, the Golden Boot, which Cruyff won.)

Footage of Cruyff signing for Feyenoord is still difficult viewing. A psychiatrist would have a field day as the chairman, Gerard Kerkum, nervously and coldly speaks to the press as Cruyff sits awkwardly, waiting for a pen. Feyenoord coach Thijs Libregts looks like he’s waiting on a bus to take him to the dentist for root canal surgery.

Perhaps the fear had set in as the chairman pondered over the deal and wondered why they had even considered making any kind of approach to Cruyff. What if there was another coup? Maybe they remembered the first time he left Ajax. Cruyff had constantly placed demands on his teammates despite not being a coach, so they revolted, stripped him of his captaincy, and Cruyff, feeling betrayed, headed to Barcelona.

Why had Cruyff accepted the offer from Feyenoord? Had anyone considered the prospect of how much this could go wrong? From Cruyff’s perspective, he would be thinking about the time Ajax were holding out and determined to sell him to Real Madrid. He threatened to quit if they didn’t sell him to the Catalans. This was well before player power; Cruyff knew his worth and his own mind. He was older in 1983 and his move to Feyenoord might have been difficult – but he knew he could do it.

The natives were already restless and slightly confused with it all. For home games, attendances weren’t improving as much as expected, initially only increasing by two or three thousand. The away fixtures though had all sold out.

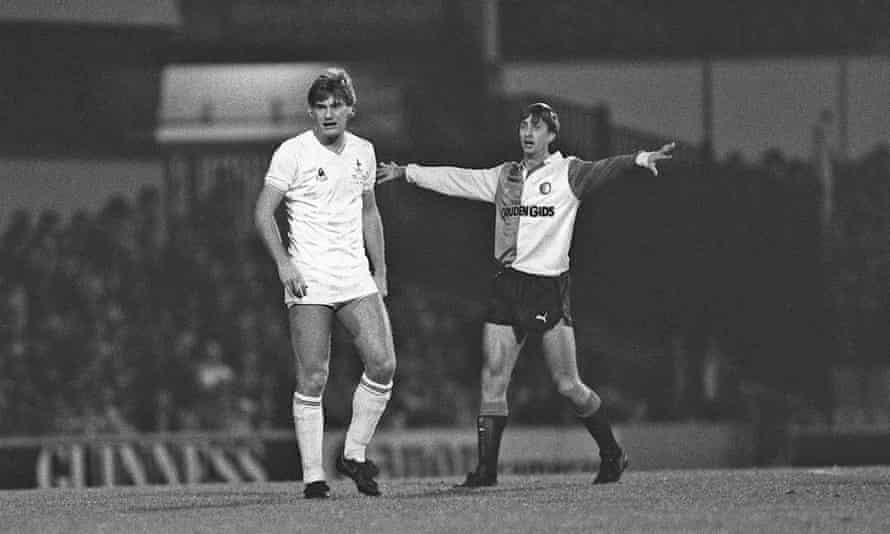

Cruyff knew what he had to do when he played his first game for Feyenoord. He had to win the fans over. He understood he was the bad guy. “I had to convince the fans of my loyalty and make sure that we won. Just as I did at Barcelona, the Los Angeles Aztecs, Washington Diplomats and Ajax, I managed to win them over during my first match. I scored a great goal in what was then the Rotterdam Tournament. Everyone started cheering. Then they suddenly seemed to realise they were cheering for someone they hated. For a moment the whole stadium was in a state of total confusion but the ice was broken when they saw how happy my teammates were. To round everything off nicely, we went on to win the tournament.”

However, when he played his first home game at De Kuip, in front of the hardcore Feyenoord fans, it was different. The supporters who attend league games don’t tend to enjoy family-friendly competitions and invitational pre-season tournaments. There’s less chance of a fight for a start. In the first league game, fans had placed banners out to let Cruyff know, in no uncertain terms, what they truly thought of him. One of the few polite ones read ‘Feyenoord Forever Cruyff Never’. Another advised ‘Cruyff Get Lost’, while others were more stark with their advice and instruction to the board and player, in language more befitting of the docks. News footage of the time had images of the hardcore fans unhappy as they ripped up season tickets for the cameras.

Cruyff’s main concerns were his fitness and age. He was an experienced athlete who had played for over three decades and knew his body. He may also have considered the period between 1979 and 1981, with the time off, moving to America, briefly helping at Ajax, then Levante, as an extended break with games as paid exercise. Cruyff would know that this period and then playing at a lower standard in America had bought his career at least another few years.

It was still a colossal gamble for both Feyenoord and Cruyff. However, the fans and board of the club had failed to factor in one crucial component. They didn’t understand the depth of Cruyff’s ferocity and vindictiveness at what he saw as an act of betrayal. He wasn’t even driven by money now, but a determination to prove Ajax wrong for daring to assume he was finished.

Fierce Genius: Cruyff’s Year at Feyenoord by Andy Bollen, published by Pitch Publishing on 15 February, £19.99

from Football | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3paBifR

via IFTTT

No Comment